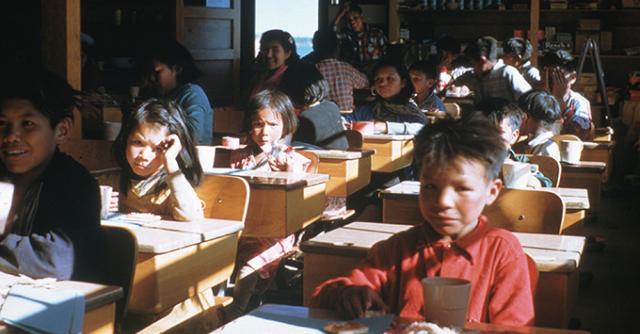

In the 19th and 20th century, the Canadian federal government's Indian Affairs department officially encouraged the growth of the Indian residential school system as a valuable agent in a wider policy of assimilating Aboriginal peoples in Canada into European-Canadian society.

A key goal of the system, which often separated children from their families and communities, has been described as cultural genocide or "killing the Indian in the child".

Although education in Canada had been allocated to the provincial governments by the British North America BNA act, aboriginal peoples and their treaties were under the jurisdiction of the federal government. Funded under the Indian Act by the then Department of the Interior, a branch of the federal government, the schools were run by churches of various denominations—about 60 per cent by Roman Catholics, and 30 per cent by the Anglican Church of Canada and the United Church of Canada, along with its pre-1925 predecessors, Presbyterian,

Congregationalist and Methodist churches.

This system of using the established school facilities set up by missionaries was employed by the federal government for economical expedience. The federal government provided facilities and maintenance, and the churches provided teachers and education.

The foundations of the system were the pre-confederation Gradual Civilization Act (1857) and the Gradual Enfranchisement Act (1869). These assumed the inherent superiority of British ways, and the need for Indians to become English-speakers, Christians, and farmers. At the time, many Aboriginal leaders wanted these acts overturned.

Specific laws also linked the apparatus of the residential schools to the compulsory sterilization of students in 1928 in Alberta and in 1933 in British Columbia. Although some academic articles currently offer rough estimates of the numbers of sterilizations the review of archival documents that would produce more specific numbers is incomplete and ongoing.

In February 2013, research by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission revealed that at least 3,000 students had died, mostly from disease. In 2011, reflecting on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's research, Justice Murray Sinclair told the Toronto Star: "Missing children — that is the big surprise for me. That such large numbers of children died at the schools. That the information of their deaths was not communicated back to their families."In a legal report, the Canadian Bar Association concludes that "Student deaths were not uncommon".

The system was designed as an immersion program: in many schools, children were prohibited from (and sometimes punished for) speaking their own languages or practicing their own faiths. In the 20th century, former students of the schools have claimed that officials and teachers had practiced cultural genocide and ethnocide. Because of the relatively isolated nature of the schools, there was an elevated rate of physical and sexual abuse. Corporal punishment was often justified by a belief that it was the only way to "save souls", "civilize" the savage, or punish runaways who, if they became injured or died in their efforts to return home, would leave the school legally responsible for whatever befell them. Overcrowding, poor sanitation, inadequate heating, and a lack of medical care led to high rates of influenza and tuberculosis; in one school, death rates reached 69%.

Federal policy tying funding to enrollment numbers may have made things worse, as it led to sick children being enrolled in order to boost numbers, thus introducing and spreading disease. Details of the mistreatment of students had been published numerous times throughout the 20th century. Following the government's closure of most of the schools in the 1960s, the work of indigenous activists and historians led to greater awareness by the public of the damage which the schools had caused, as well as to official government and church apologies, and a legal settlement. This has been controversial both within indigenous and non-indigenous communities.

Modern Day School System

The Reforming First Nation Education Initiative supports improved educational outcomes for First Nation students. The initiative will shape future directions in education program reform through two proposal-based programs: the First Nation Student Success Program and the Education Partnerships Program. For the first year of submissions under the Reforming First Nation Education Initiative, the department approved a total of 37 proposals from across Canada: 18 for the First Nation Student Success Program and 19 for the Education Partnerships Program.

The selected projects, as well as new ones funded in subsequent rounds of the program, will help to promote collaboration between First Nations, provinces, INAC, and other stakeholders.

The First Nation Student Success Program is designed to support First Nation educators on reserve (Kindergarten to Grade 12) in their ongoing efforts to meet their students' needs and improve student and school results. In particular, the program will help First Nation educators to plan and make improvements in the three priority areas of literacy, numeracy and student retention.

The Education Partnerships Program is designed to promote collaboration among First Nations, provinces, the Government of Canada and other stakeholders in order to improve the success of First Nation students in First Nation and provincial schools. It will do this through support for partnership arrangements, where First Nation and provincial officials share expertise and services, and partners coordinate learning initiatives.

“I am proud of the programs and partnerships that are possible because of the Reforming First Nation Education Initiative,” said Minister Strahl. “By focussing on literacy, numeracy and student retention, the projects moving forward will help form the foundation for long-term improvements in First Nation education.”

In December 2008, the Government of Canada committed $268 million over five years to the Reforming First Nation Education Initiative, with a further $75 million in ongoing funding. Both the First Nation Student Success Program and the Education Partnerships Program are integral to the Government of Canada's commitment to improve educational outcomes for First Nation learners.

Under the first round of proposals for the First Nation Student Success Program, approximately $25.9 million has been approved for projects that will help First Nations make improvements in literacy, numeracy and student retention. Under the Education Partnerships Program, approximately $4.4 million has been approved to support the establishment and advancement of formal tripartite partnership arrangements that aim to develop practical working relationships between officials in regional First Nation organizations and schools, and those in provincial systems.

Through this initiative more than 70 per cent of First Nation communities, representing all regions across Canada, are receiving funding. Applications for the second round of proposals under the two programs are currently being evaluated.